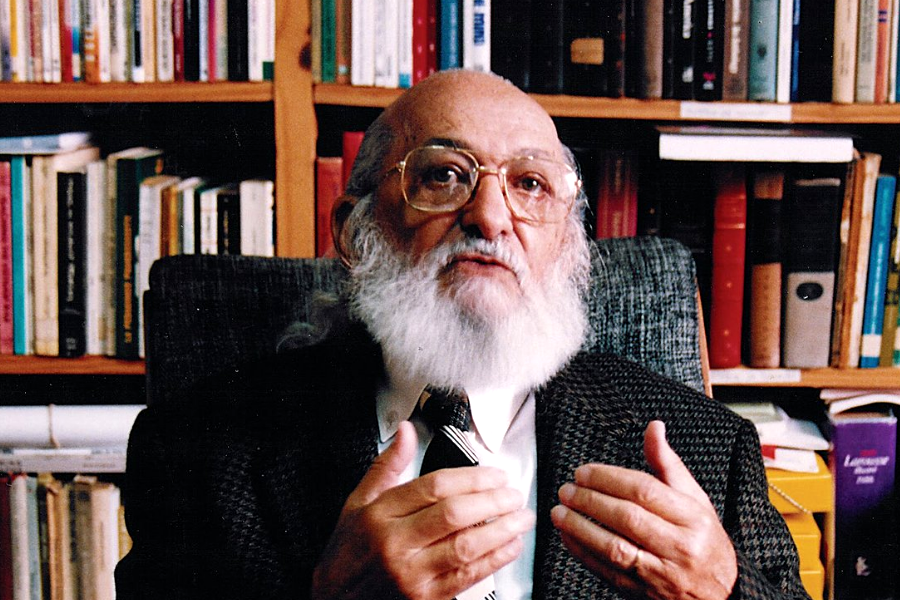

Paulo Freire´s Centenary: his legacy as educator is vital for strengthening Y&AE for democracy

September 1, 2021During September, the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE) developed a campaign through communication, awareness and dialogue activities in order to remember the importance of the legacy of the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire and reaffirm our option and struggle for a liberating education that strengthens democracy and promotes social transformation, towards a more just, equitable, sustainable and peaceful world.

CLADE is a plural network of civil society organizations, with presence in 18 Latin American and Caribbean countries and, from its founding moment, has assumed the thought and pedagogy of Paulo Freire as one of its main principles for the struggle for the human right to education in the region.

Emancipatory education, critical thinking, the transformation of educational environments and relationships into spaces for the collective construction of knowledge, reading of contexts, search for alternatives and transforming actions within the horizon of democracy, have been at the core of CLADE’s strategic work.

Within this framework and having in mind the centenary of Paulo Freire, celebrated on September 19, CLADE, articulated with the Latin American and Caribbean Campaign in Defense of Paulo Freire’s Legacy, organized by the Council for Popular Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (CEAAL), developed a month of communication, awareness and dialogue actions, to recall the importance of Freire’s legacy for the guarantee of an emancipating and critical education, which strengthens democracies in our continent and around the world.

Each week of the month, starting on September 3, CLADE members conducted and disseminated webinars, messages and materials in various formats shared through social media and other channels, as well as interviews and conferences, in order to highlight different concepts related to Freire’s legacy for the realization of an emancipatory and democratic education.

The last week of the campaign, from September 25 to 30, highlighted activities and messages about Freire’s legacy for the guarantee of Youth and Adult Education (Y&AE) as a key fundamental human right to promote sustainable development, human rights and, with them, our democracies.

In this framework, the Platform of Regional Networks for Youth and Adult Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, of which CLADE is a member, together with the Latin American Association of Popular Education and Communication (ALER), CEAAL, the International Federation Fe y Alegría (FIFyA), the Network of Popular Education Among Women in Latin America and the Caribbean (REPEM) and the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE), with the sponsorship of DVV International and Open Society Foundations, held a webinar on September 30, from 17h to 19h (Brazil time, GMT-3), to take up, disseminate and discuss the struggles, demands and proposals of the subjects and activists of Y&AE in Latin America and the Caribbean, on the way to the International Conference on Adult Education (Confintea) VII, which will take place in 2022 in Morocco.

The event, addressed, among other aspects, the importance of Freire’s legacy for the guarantee of Y&AE as a human right, popular and transformative education in the Freirean perspective and the situation of Youth and Adult Education in Latin America and the Caribbean in the context of pandemic.

See below de record of this event in English:

Freire’s contributions to Y&AE: towards sustainable development and social and environmental justice

Inspired by Paulo Freire’s perspectives and teachings, and with Confintea VII on the horizon, members of the Regional Networking Platform for Y&AE in Latin America and the Caribbean advocate for a new Y&AE, which should be popular, free, secular, inclusive, emancipatory and transformative. An education that shouldn’t have colonial, sexist, patriarchal and racist features.

In front of welfare and remedial approach that is usually given to Y&AE, we defend that this educational modality must be of quality, with cultural and social relevance. In front of onslaught of tendencies that attempt to privatize education, the right to Y&AE must be guaranteed free of charge. Their homogenizing vision must be overcome with the conception of Y&AE based on the valuation and exercise of education in its multiple expressions. From this point of view, Y&AE not only has a high educational value, but is also a commitment to the transformation of reality, to the change of social structures. Faced with different forms of discrimination and exclusion of a structural nature, this educational modality must contribute to lay the foundations for our societies, which shouldn´t be colonial, patriarchal and racist.

In times in which the motivations for continuing studies, mainly of people over 15 years of age, have been transformed and go far beyond the fulfillment of academic training needs, the priority of Y&AE should be community, permanent and popular education because it is carried out with and in all areas where human beings develop their activities. Furthermore, it takes community processes as the basis for educational objectives and is committed to the process of popular movements and the overcoming of all forms of oppression. Thus, Y&AE should stop concentrating on formal education and give priority to non-formal and popular education, promoting the social construction of knowledge in communities that foster intercultural, intergenerational and intersectoral encounters.

From this perspective, which is in line with Freire’s thought, the new understandings of Y&AE are based on conceiving human beings as subjects of education capable of producing the urgent and necessary changes for the construction of a more just and sustainable society.

For these reasons, and in compliance with the principles of lifelong education, governments should recognize education throughout life and for the diversity of the population as a human right, guaranteeing its full functioning through public policies, institutions and pertinent resources. Literacy, being the basis for the continuity and completion of studies, mainly of the sectors with higher levels of vulnerability, in current times, requires a broad and diverse vision and educational offer that guarantees the continuity of studies at all levels and areas of the educational systems, overcoming the traditional basic literacy approaches, recognizing learning developed in daily life and developing educational processes from the culture and mother tongue.

On the other hand, assuming the challenges of the current context of multiple crises and the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the daily life of humanity, we propose to rethink an Y&AE whose principles should be the following: education to create harmonious relationships among human beings, community and mother earth, to enjoy health with integral well-being, and to contribute to develop a resilient society, which preserves the existence of all living beings; a liberating and transforming Y&AE, as part of social and popular movements and as a political-educational strategy and project, in such a way that people and communities become active subjects of the required transformations of the planet; education for the construction of a society free of all kind of discrimination, inequality and exclusion; a community and democratic Y&AE, for coexistence, participatory democracy and socio-community participation; an education based on social justice and political, social, cultural, economic and environmental rights of individuals, peoples and nature.

In other words, we defend an education and Y&AE for the encounter among cultures, that overcomes inequalities derived from colonialism, for intercultural dialogue and revaluation of collective knowledge. Based on Freire’s legacy, the transformative education we need, to build the world we want, is one that guarantees the right to know and the accumulated knowledge of humanity and science, with its use for the benefit of all people, from critical pedagogies and cultural dialogue for global citizenship, the defense of rights, peace, common goods and the care of our common home.

>> Read more in our regional statement towards Confintea VII (available in Spanish).

COVID-19: CLADE considers that solidarity and adequate funding for the rights to education, health, and social protection are key to overcome the crisis

March 25, 2020Considering the widespread crisis and state of emergency across the world due to the COVID-19 pandemia, CLADE acknowledges and appreciates the life and health prevention and care recommendations made by the World Health Organization. We would like to express our solidarity with families that have lost their loved ones due to the virus, as well as survivors and sick people. Likewise, we would like to congratulate CLADE members, as well as so many human rights organizations and movements across Latin America and the Caribbean, for promoting several initiatives to ensure the protection of education communities and their human rights. We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to health workers, as well as workers in other key areas who put their lives at risk to provide essential services. (more…)

Experts and youths talk about the right to education in Latin America and the Caribbean

March 16, 2020“The Education We Need for the World We Want: views from adolescents and youths in Latin America and the Caribbean” was the title of the virtual conversation held by the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE), with the participation of youths and authorities from Latin America and the Caribbean, who stressed challenges and proposals to ensure the right to education in this region.

(more…)

Adolescents and youths share their views on the education they want for a better world

December 19, 2019The initiative #TheEducationWeNeed for the world we want is aimed at mobilizing adolescents and youths in Latin America and the Caribbean, inviting them to tell us what education they need for a better world and the most important demands from their countries.

What are Latin America and Caribbean students’ thoughts on education and other human rights?

November 11, 2019Overcoming discrimination and violence, the right to play, art and recreation, gender equality and the right to comprehensive sexuality education and to participate in the debates on public policies affecting them: these were some of the demands shared by boys, girls, adolescents and youths during the 22nd Pan-American Child Congress and the Third Pan-American Child Forum that were held from Oct. 29-31 in Cartagena (Colombia).

(more…)

“The Convention is a moral universal instrument against injustice to which girls and boys in the world were subjected”

November 7, 2019Close to the 30th anniversary of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) to be celebrated on November 20, the president of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, which is responsible for monitoring this treaty, Luis Ernesto Pedernera; and the rapporteur on the rights of the child and president of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH), Esmeralda Arosemena de Troitiño, presented some thoughts on the advances and challenges for the implementation of the Convention.

(more…)

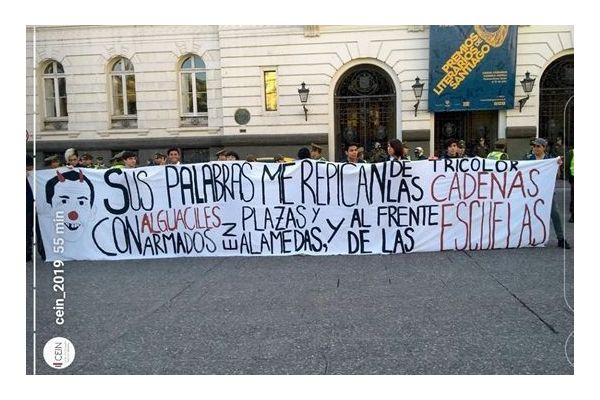

Brazil: Students, teachers unions and civil society lead the struggle for the right to education

August 16, 2019On this World Humanitarian Day, we affirm that the student, education professionals and civil society-led mobilizations that took place across the country on August 13 are a strong reaction and a sign of resistance to a government that has been making great strides towards a not desired past.

This moment is one of a huge crisis in the Brazilian democracy. Not that we haven’t experienced crisis in the past, but what we have witnessed since the impeachment of president Dilma Rousseff in 2016 is the country’s democratic foundations and institutions being weakened and a backsliding in social achievements. We had never advanced so far in strengthening democracy and advancing social rights, and we had never seen setbacks at such a rapid pace.

Chile’s “Safe Class Law”: Violence in public schools and the “regulation” of school life

August 10, 2019In 2008 UNICEF published the study “School life, an indispensable component of the right to education”, inquiring about internal regulations in educational establishments in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, Chile. The results are surprising, for example, they showed that more than 50% of the regulations did not comply with the legal order in effect, that is, they transgressed or omitted rights, in particular regarding disciplinary matters. It was also noted that the regulations were reduced to a series of rules oriented only to disciplinary issues, which did not look at the community as a whole, nor the relationships, nor the responsibilities of all levels in the construction of reality. In addition, community participation was not validated in the vast majority of them. Finally, the study recommended not using the regulations to rule life in schools, at least not as they were then (UNICEF, 2008). (more…)

Education for freedom: CLADE launches document about emancipatory education

May 21, 2019Download the document:

The publication, launched in the context of the initiative “Education for freedom”, brings together reflections and debates gathered by CLADE network on this subject, addressing the right to education from an integral and holistic perspective, in its connection with: freedom, social transformation, decolonization, democracy, gender equality, communication and technologies, arts and culture, affection and care, as well as bodies and territories.

Its reflections offer ways for an emancipatory education that contributes to the formation of societies free from all oppression, and also to transform the lives of children, adolescents, young people and adults through reflection, dialogue, critical thinking, and the skills to question, discern, imagine and act towards other possible worlds.

“Education should contribute to people being in tune with their time and space, knowing their territory, context, history and cultural diversity. Therefore, spaces and processes of informal, non-formal and formal education must be related, promoting culture and knowledge, research, education and extension, contributing to economic, social and environmental justice”, the publication points out.

Release

The document was launched on May 21 with a virtual dialogue, with the participation of Luna Contreras, popular educator and director of the Democracy and Global Transformation Program (PDTG, by its Spanish acronym) Tejiendo Saberes Perú; Martín Ferrari, an Argentine popular educator and one of the directors of the documentary “Education in movement” (Educación en Movimiento), and María Cianci, education and research coordinator of ALER. The dialogue was moderated by Rosa Zúñiga, general secretary of CEAAL.

If you weren’t able to participate in the event, you can access the recording of the dialogue (in Spanish) through the following link:

powered by Advanced iFrame. Get the Pro version on CodeCanyon.